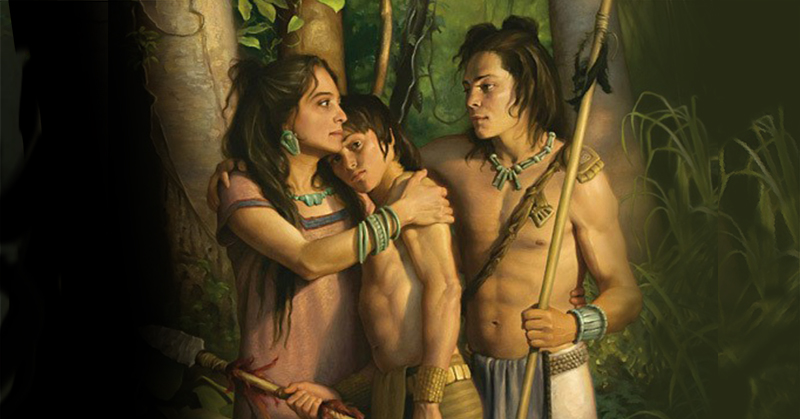

Uno de los relatos más conocidos del Libro de Mormón que inspira fidelidad y deseo de salir a realizar la obra de Dios es el de los “dos mil soldados jóvenes” (Alma 53:22). La historia que inspira a miembros de la iglesia es que estos jóvenes estuvieron dispuestos a seguir la fe que sus madres les enseñaron y a dar sus vidas por el bien del país (56:47-48). Su ejemplo muestra que con buenos líderes y una diligencia enfocada, la protección de Dios se manifiesta, inspirando un sentimiento de confianza.

Sin embargo, mirando el contexto de estos capítulos de guerra, hay más detrás de la historia que puede pasar desapercibido por los lectores. La manera en que Mormón, el historiador, compila y relata los sucesos de la historia del Libro de Mormón refleja una manera de ver el mundo antiguo lleno de diversidad étnica. Estos dos mil soldados siempre permanecieron como una unidad militar estrictamente de linaje lamanita, basado en el etnocentrismo de los nefitas. Aún así con esta marginalización, mantuvieron la fe y lograron el éxito.

¿Qué importa un nombre?

Mormón comienza diciéndole al lector que tiene “algo que decir concerniente a los del pueblo de Ammón, que en un principio eran lamanitas” (Alma 53:10). Es posible que a quienes no han investigado el etnocentrismo de los nefitas les costará ver el mensaje detrás de los títulos sobre este pueblo. Ellos “eran lamanitas” antes pero ahora eran el “pueblo de Ammón” (no se menciona el título de anti-nefi-lehitas [Alma 23:17]). El punto que resalta es que no eran nefitas.

En la historia del Libro de Mormón, los nefitas (y zoramitas) inicuos “se hicieron lamanitas” (Alma 43:4). En inglés (la traducción que hizo José Smith) dice, “became Lamanites”, o sea, “llegaron a ser lamanitas”. Sí, muchos llegaron a ser “lamanitas, los cuales eran un conjunto de los hijos de Lamán y Lemuel y los hijos de Ismael, y todos los disidentes nefitas, que eran amalekitas y zoramitas, y los descendientes de los sacerdotes de Noé” (énfasis añadido; Alma 43:13; véase también Helamán 3:16). Un nefita pecador podía llegar a ser lamanita. En cambio, los lamanitas solamente podían dejar de ser lamanitas de nombre; es decir, “dejaron de ser llamados lamanitas” (énfasis añadido; Alma 23:17). Ellos no llegaron a ser nefitas, ni siquiera llegaron a ser llamados así. Seguían siendo lamanitas llamados por otro nombre, y en la historia del Libro de Mormón, solo hubo igualdad cuando se borraron los -itas del pueblo (4 Nefi 1:17).

Tomando esta actitud nefita en cuenta, seguramente Mormón quiso hacer hincapié cuando dijo que los dos mil jóvenes “se hicieron llamar nefitas” (énfasis añadido; Alma 53:16). No llegaron a ser nefitas, ni siquiera fueron llamados nefitas por los mismos nefitas. Estos jóvenes fieles se autodenominaron “nefitas”. Así se identificaron. Usualmente, los jóvenes que han vivido por muchos años en un país que no es el de sus padres han hecho lo mismo. Al ser criados en un país extranjero, dicha nación llega a ser la suya propia y adoptan su cultura. Comúnmente, esa nueva cultura se mezcla con la de sus padres migrantes. Aquí uno puede ver que eran tanto lamanitas de sangre como culturalmente nefitas en un país nefita.

Algunas páginas antes, Mormón dice que era el “año decimoquinto” cuando el pueblo de Ammón ya estaba en Jersón (tierra nefita; Alma 28:7). Luego en el “año veintiocho” estos jóvenes van a la guerra (Alma 53:22-23), o tal vez en el “año veintiséis” (Alma 56:9). Significa que pudieron haber vivido de once a trece años en tierra nefita. Además, todavía eran muy jóvenes y por eso Helamán les llama “pequeños hijos” (énfasis añadido; Alma 56:30). Todavía eran pequeños y llevaban toda la vida en tierra nefita. Así que tenían todo el derecho de hacerse “llamar nefitas”, y aún más después de alistarse a defender el país nefita, o sea, su país.

Inclusive sus padres extranjeros decían que era su hogar. Cuando la guerra se tornó opresiva, “se llenaron de compasión y sintieron deseos de tomar las armas en defensa de su país” (énfasis añadido; Alma 53:13) y “sus hermanos” (Alma 53:15). Sin poder pelear ellos debido al convenio que habían hecho de no portar armas, sus hijos “concertaron [un] convenio y tomaron sus armas de guerra para defender su patria” (énfasis añadido; Alma 53:18). Pero Mormón observa que aunque comparten un país la gente no está tan unida como uno quisiera hoy día. Al resumir el covenio mencionado arriba, el lenguaje implementado muestra que estos jóvenes se identificaron como gente diferente a los otros nefitas. “E hicieron un convenio de luchar por la libertad de los nefitas … sí, hicieron convenio de que jamás renunciarían a su libertad, sino que lucharían en toda ocasión para proteger a los nefitas y a sí mismos del cautiverio” (énfasis añadido; Alma 53:17). Hicieron convenio de defender a los nefitas y a sí mismos, mostrando una distinción. Aunque “se hicieron llamar nefitas” reconocieron que no eran como los otros nefitas. Mormón dice claramente que ellos desearon defender a su país/patria pero no que solo defenderían a su pueblo (en referencia a toda la gente en tierras nefitas).

Ammorón no parece tener el mismo problema. Cuando le escribe a Moroni, dice con un tono de orgullo: “Soy Ammorón, y soy descendiente de Zoram, aquel a quien vuestros padres obligaron y trajeron de Jerusalén. Y he aquí, soy un intrépido lamanita” (énfasis añadido; Alma 54:23-24). Ammorón podía identificarse tanto como descendiente de Zoram como Lamanita, y nadie lo ponía en duda (Alma 43:13). Los dos mil se hicieron llamar nefitas, pero nadie más lo hizo, ni Helamán su caudillo, ni Mormón el historiador, mucho menos sus padres. No debe sorprender al lector que nadie más les llama nefitas. Esta marginalización implementada por los nefitas no es nada nuevo.

Etnocentrismo nefita

Otros han visto esta desigualdad proveniente de los nefitas. El erudito John Sorenson, hablando de la mezcla entre los mulekitas y los nefitas, dijo:

“Se habla tan poco de los mulekitas, aunque compusieron una mayoría de la población bajo los gobernantes nefitas (Mosíah 25:12), que debemos suponer que constituyeron un campesinado que fueron ignorados por los niveles de élite (nefitas) de la sociedad de la cual vinieron los historiadores”1.

Viéndolo bien, los mulekitas casi desaparecen como pueblo en la historia nefita.

Referente al uso de la palabra “desierto” entre los nefitas, Kirk Magleby ha observado:

“Si las autoridades en Nefi o Zarehemla no ejercen dominio sobre un área, se podría clasificar como desierto. En otras palabras, desierto era territorio fronterizo que carecía de leyes y civilización (según lo definían los autores del texto). Por ejemplo, cuando el capitán Moroni expulsó a los lamanitas del desierto del este, ellos habían construido fortificaciones ahí (Alma 50:11), pero como no eran fortificaciones nefitas, el cronista Helamán1 (compilado por Mormón) llamó al lugar ‘desierto’”2.

Sobre el rechazo de Samuel y su apodo de “el lamanita”, Max Perry Mueller ha escrito:

“Samuel es rechazado porque Zarahemla es una ciudad segregada. No obstante, tal como las profecías de Samuel indican, es posible que Zarahemla esté segregada basada en niveles de rectitud como también en tonos de color de piel. Al fin de cuentas, los lamanitas tiene su propio país, donde ‘la mayor parte de ellos’, explica Mormón, ‘se esfuerzan por guardar sus mandamientos y sus estatutos y sus juicios, de acuerdo con la ley de Moisés’ [Helamán 15:5-6]. … Samuel, el lamanita grita desde los muros de Zarahemla a los nefitas abajo, acusándoles de rechazarlo ‘porque [es] lamanita’ [Helamán 14:10]”3.

Mueller también describe la manera en que los historiadores y líderes religiosos nefitas fueron reprendidos por el Señor por no incluir en sus Escrituras las profecías de Samuel el lamanita:

“Es paradójico que en el Libro de Mormón no es un nefita sino Samuel quien profetiza más acertadamente sobre la venida de Cristo y el significado de su misión terrenal, muerte y resurrección. … Durante su visita a las Américas (alrededor de 34 d. C.), el Cristo resucitado examina los textos sagrados de los nefitas, y los encuentra deficientes. … Jesucristo con tan solo mirar el registro exige, ¿dónde están las profecías de ‘mi siervo, Samuel el lamanita’? En tono sarcástico, Cristo le pregunta a Nefi3, ¿‘No fue así’ que él le había mandado a Samuel que ‘testificara’ a los nefitas que el sacrificio expiatorio de Cristo está disponible no solo a todo pueblo en todas partes sino también a todo pueblo en toda época? … De parte de Samuel, Cristo reprende a los nefitas por no haber ‘escrito esto’, la profecía de Samuel, en el archivo sagrado del pueblo [3 Nefi 23:9-11]” (énfasis original; ibíd, 49).

Los nefitas no habían guardado ni mantenido como sagradas las profecías de un lamanita. La información provista en el texto indica que el pueblo de Nefi era nefita-céntrico.

Incluso el relato del pueblo de Ammón indica esto. Cuando estos lamanitas se convirtieron al Señor, Mormón dice que “sucedió que se pusieron el nombre de anti-nefi-lehitas; y fueron llamados por ese nombre, y dejaron de ser llamados lamanitas” (Alma 23:17). Mantuvieron este nombre mientras seguían independientes (Alma 27:25), antes de descender a la tierra de Jersón: “Y descendieron a la tierra de Jersón, y tomaron posesión de esa tierra; y los nefitas los llamaron el pueblo de Ammón; por tanto, se distinguieron por ese nombre de allí en adelante” (énfasis añadido; Alma 27:26). El nombre de Anti-Nefi-Lehi no se vuelve a mencionar hasta que Mormón aclara que el nombre que habían escogido para ellos mismos se cambió por otro: eran el pueblo de Anti-Nefi-Lehi, quienes fueron llamados el pueblo de Ammón. Y Mormón da la razón por la que abandonaron (o les fue quitado) el nombre que ellos mismos se habían puesto: “los nefitas los llamaron el pueblo de Ammón” (Alma 27:26). Los nefitas les cambiaron el nombre.

En este caso, el verbo “fueron” en puede interpretarse de dos maneras: “fueron” y seguían siendo o “fueron” porque habían sido antes. Mormón indica que recibieron un cambio de nombre cuando llegaron a tierras nefitas. Primero, “el juez superior envió una proclamación por todo el país, en la que deseaba saber la voz del pueblo respecto a la admisión de sus hermanos, que eran el pueblo de Anti-Nefi-Lehi” (Alma 27:21). Justo después, dice “que el pueblo de Ammón quedó establecido en la tierra de Jersón” (énfasis añadido; Alma 28:1). En otras palabras, pidieron entrar como el “pueblo de Anti-Nefi-Lehi” pero les fue permitido permanecer como el “pueblo de Ammón”. Parece indicar que parte de la “condición” (Alma 27:24) para entrar era no llamarse “anti-nefi-lehitas”, tal vez para no asociarse con el nombre de Nefi.

Y hay más. Los nefitas de Zarahemla les conceden “la tierra de Jersón, que se halla al este junto al mar” (Alma 27:22). En el texto está claro que Zarahemla quedaba en “el centro de sus tierras” (Helamán 1:18). Por tanto, siguiendo el modelo de geografía del Libro de Mormón que el lector desee, si Zarahemla se encuentra en “el centro de sus tierras” poner a un pueblo “junto al mar” (cualquiera de los dos) sería ponerlos lo más lejos posible de la capital. Los nefitas no solo hicieron esto con el pueblo de Ammón. Aún después de que el pueblo de Ammón había salido de Jersón (Alma 35:13), los nefitas siguieron juntando en un solo lugar a otros lamanitas que hicieron pacto con ellos. Mormón después dice que “cuando [otros lamanitas] hubieron hecho este pacto, los enviaron a habitar con el pueblo de Ammón” (énfasis añadido; Alma 62:17), los lamanitas con los lamanitas. Estos jóvenes se habían criado en un país que hacía diferenciación entre nefitas y ellos mismos.

Helamán y “los hijos de aquellos hombres”

Como caudillo, escogen a Helamán (Alma 53:19), un hombre noble que sería muy pronto un héroe. Sin embargo, ningún ser humano es perfecto, y Mormón demuestra su desarrollo. Cuando le escribe al capitán Moroni, Helamán hace hincapié en explicar que estos jóvenes no eran nefitas. Describiéndolos, él dice que eran “dos mil de los hijos de aquellos hombres que Ammón trajo de la tierra de Nefi —y ya estás enterado de que estos eran descendientes de Lamán, el hijo mayor de nuestro padre Lehi; y no necesito repetirte concerniente a sus tradiciones ni a su incredulidad, pues tú sabes acerca de todas estas cosas” (énfasis añadido; Alma 56:3-4).

Helamán no dice que eran nefitas, sino que dice de manera insensible que eran hijos de “aquellos hombres” (es decir, de los lamanitas). Ni si quiera los identificó como el pueblo de Anti-Nefi-Lehi que “Ammón trajo”. Después, cuando estos jóvenes tienen éxito le dice a Moroni, “jamás había visto yo tan grande valor, no, ni aun entre todos los nefitas” (énfasis añadido; Alma 56:45). En otras palabras, “jamás había visto yo tan grande valor [entre los lamanitas], no, ni aun entre todos los nefitas”, haciendo distinción entre sus dos mil y los demás. Es la misma distinción que habían hecho los jóvenes antes (Alma 53:17). Seguramente, Helamán no lo hacía conscientemente. Solo era parte de la cultura nefita. Pero uno puede notar un comportamiento transformador en contra de la norma cuando también enfatiza su propia relación con ellos: “mis dos mil hijos (porque son dignos de ser llamados hijos)” (Alma 56:10). No obstante, parece que siente la necesidad dar una razón justificándose por llamar a estos lamanitas “hijos”: “porque son dignos”.

Hay un pasaje que se puede leer de dos maneras, ambas a favor de esta perspectiva. Relatando los logros del ejército, Helamán dice: “…nosotros, el pueblo de Nefi, la gente de Antipus y yo con mis dos mil, rodeamos a los lamanitas y los matamos” (Alma 56:54). La versión original del Libro de Mormón, transcrita por Oliver Cowdery, no tenían puntuación, o sea, comas. Por lo tanto, puede ser que el “pueblo de Nefi” se constituye de “la gente de Antipus” y “yo con mis dos mil”, de acuerdo con la puntuación moderna. Así estaría incluyendo a los dos mil en el pueblo de Nefi, un concepto revolucionario. Por otro lado, también existe la posibilidad de que Helamán esté distinguiendo entre los dos grupos, identificándose con ambos: “nosotros el pueblo de Nefi [que incluye] la gente de Antipus y [también] yo con mis dos mil”. Puede ser que usa “nosotros” para identificarse con los nefitas y dice “yo” para mostrar que está acompañando a los dos mil soldados lamanitas. Ambos funcionan. Helamán puede estar haciendo el esfuerzo de mostrarle a Moroni que los dos mil son parte del pueblo de Nefi. O, puede estar marcando la distinción conforme a la sociedad dominante.

Soldados ignorados

Si lo anterior es un resumen correcto de los hechos, tiene que haber más detalles en el registro que confirmen tal conducta nefita. El texto está claro, Moroni se entera por primera vez de estos jóvenes soldados a través de la carta de Helamán, que se registra en los capítulos 56 al 58 del libro de Alma. Helamán comienza diciendo que “en el año veintiséis, yo, Helamán, marché al frente de estos dos mil jóvenes” (Alma 56:9). Mormón dice que esto pasó en el “año veintiocho” (Alma 53:22-23). No fue hasta “principiar el año treinta del gobierno de los jueces, el segundo día del primer mes, [que] Moroni recibió una epístola de Helamán” (énfasis añadido; Alma 56:1). Dependiendo de la fecha, fuera el año veintiséis o el veintiocho, pudieron haber pasado dos a cuatro años antes de que Moroni, el capitán del ejército, supiera de la compañía milagrosa de Helamán. Para cualquier militar, esto suena extraño, aún para un ejército de la antigüedad. Es posible que los únicos que supieron en las tierras nefitas de este grupo eran los soldados que pelearon al lado de ellos y sus mismos padres que los vieron salir a la guerra. (Después la posibilidad de que Pahorán supiera muy bien de ellos será propuesta.)

Es sorprendente que el capitán Moroni no supiera de ellos. Por otro lado, es probable que el rey Ammorón estaba muy consciente de la compañía ammonita-lamanita. Helamán escribió que recibió “una epístola del rey Ammorón” (Alma 57:1), tal vez porque había llegado a ser el nuevo comandante después de la muerte de Antipus (Alma 56:51). Esta carta no llegó a nadie más. Por consiguiente, el rey de los lamanitas, de sangre nefita, pudo haber sabido de la banda de Helamán de soldados de sangre lamanita, mientras que el capitán Moroni se hallaba en la ignorancia. Aunque en la guerra la comunicación es difícil y las distancias limitan, cuatro años es mucho tiempo para no saber de un grupo que ha tenido tanto éxito milagroso.

Una compañía lamanita en un ejército nefita

Literalmente líneas después de relatar a Moroni que en su área quedaron “prevenidos con diez mil hombres” (Alma 56:28), “Antipus me dio la orden de salir con mis pequeños hijos hacia una ciudad inmediata” (Alma 56:30). Había diez mil hombres, contando o no a los dos mil jóvenes y llegó la orden que solo los “pequeños hijos” de Helamán fueran a la ciudad de Antipara. Esa era su compañía en el ejército, de una sola raza. Esto era común en la antigüedad y pueden encontrarse casos similares en tiempos modernos también (La Segunda Guerra Mundial).

Como indican las palabras de Helamán, a pesar de llegar más refuerzos, esta compañía de soldados siempre terminaba siendo de raza lamanita: “Y sucedió que a principios del año veintinueve, recibimos … un refuerzo de seis mil hombres para nuestro ejército, además de sesenta de los hijos de los ammonitas que habían llegado para unirse a sus hermanos , mi pequeña compañía de dos mil. Y he aquí, éramos fuertes” (énfasis añadido; Alma 57:6). Helamán afirma que los refuerzos llegaron para “nuestro ejército”. Pero, aunque llegaron varios grupos de miles soldados, nunca se quedaron con sus dos mil. De todos los miles que llegaron, solamente los “sesenta de los hijos de los ammonitas” son los que se quedan con los dos mil.

El siguiente movimiento los deja abandonados. Helamán dice que escogen (“escogimos”, o sea que él fue parte de la decisión) “una parte de nuestros hombres, y les encargamos nuestros prisioneros para descender con ellos a la tierra de Zarahemla” (Alma 57:16). Después está claro que ninguno de los dos mil sesenta acompañaron al grupo que fue escogido a ir a Zarahemla porque Helamán seguía con “mi pequeña compañía de dos mil sesenta” (Alma 57:19). Después de llegar seis mil hombres, la compañía ammonita-lamanita solo recibió los sesenta que eran de la misma raza que ellos. Y esto aún después de decir Helamán que “incorporé [a los hombres de Antipus] con mis jóvenes ammonitas” (Alma 56:57). Parece que no quedaron incorporados por mucho tiempo. Evidentemente, no eran simplemente una compañía en el ejército nefita; eran una compañía exclusivamente de lamanitas en el ejército nefita. En ningún momento los refuerzos nefitas se unieron al grupo de ammonitas-lamanitas, sino tal vez hasta que después el problema fuera arreglado.

El desinterés de Pahorán

Es posible que muchos lectores no hayan visto estos detalles antes en el texto. Después de varias victorias, la captura de Antipara (Alma 57:1-4) y Cumeni (Alma 57:7-12), Helamán expresa que no está recibiendo los abastecimientos que necesita, tal vez para mantener tantas ciudades ya conquistadas. Él le dice a Moroni que “la causa de estos aprietos nuestros, o sea, el motivo por el cual no nos mandaban más fuerzas, nosotros lo ignorábamos” (Alma 58:9).

El capitán Moroni adopta este problema y lo hace suyo. Le envía una carta a Pahorán reclamándole, diciendo: “Y he aquí, os digo que yo mismo, y también mis hombres, así como Helamán y sus hombres, hemos padecido sumamente grandes sufrimientos; sí, aun hambre, sed, fatiga y aflicciones de toda clase” (Alma 60:3). Cuesta entender que Moroni haya estado sufriendo también como su carta implica y que solo haya reaccionado así después de recibir la carta de Helamán. Es más probable que Moroni, igual Lehi y Teáncum cerca del mar este (Alma 27:22 ; 52:18), recibía tanto hombres como provisiones. El área que no los recibía era el sector de Helamán en el sur, cerca del mar del oeste (Alma 53:22). Por lo tanto, Moroni reacciona así por el maltrato de los soldados, bajo el mando de Helamán. Y el mismo historiador Mormón lo dice: “Y sucedió que inmediatamente envió una epístola a Pahorán, solicitando que hiciera reunir hombres para fortalecer a Helamán, o sea, los ejércitos de Helamán” (énfasis añadido; Alma 59:3). Los necesitados de víveres y hombres no eran Moroni, Lehi o Teáncum. Los que no habían sido fortalecidos suficientemente por el gobierno eran los ejércitos del sector de Helamán.

Aunque es cierto que Pahorán afirma haber sido destronado por Pacus (Alma 61:3-5) y Moroni confirma que es cierto (Alma 62:6), Pahorán no se escapa de la culpa. La comunicación entre Moroni y Pahorán revela que los ejércitos de Helamán no eran su prioridad. El propósito de la carta de Moroni fue conseguir provisiones para Helamán, mencionándolo por nombre tres veces (Alma 60:3, 24, 34). En cambio, en la carta de Pahorán, él no menciona a Helamán una sola vez (Alma 61). Es más, él sugiere un plan para que Moroni lo rescate a él y que lleven víveres solo a Lehi y a Teáncum, dejando a Helamán en el olvido, quien era la razón de la carta de Moroni. Con ánimo, Pahorán dice: “Y nos apoderaremos de la ciudad de Zarahemla a fin de obtener más víveres para enviar a Lehi y a Teáncum; sí, marcharemos contra ellos con la fuerza del Señor, y daremos fin a esta gran iniquidad” (énfasis añadido; Alma 61:18). Sus últimas palabras muestran su verdadera preocupación: “ Procura fortalecer a Lehi y a Teáncum en el Señor; diles que no teman porque Dios los librará, sí, y también a todos aquellos que se mantienen firmes en esa libertad con que Dios los ha hecho libres. Y ahora concluyo mi epístola a mi amado hermano Moroni” (Alma 61:21). A quienes Pahorán quería fortalecer eran Lehi y Teáncum solamente. Seguramente, él tenía motivos por estar preocupado por la guerra en el oeste, pero eso no justifica haber ignorado por completo la situación de Helamán. No está claro a quién hacía referencia cuando dijo “todos aquellos” (véase arriba). Por un lado, pueden ser los ejércitos nefitas de Lehi y Teáncum, y si es así, conscientemente ignoró a los hombres de Helamán. Por el otro lado, si “todos aquellos” son los ejércitos de Helamán, Pahorán no vio importante mencionarlos específicamente.

Puede referirse a los soldados ammonitas-lamanitas, ya que Helamán le había enviado una embajada antes (Alma 58:4), cuyos hombres nunca regresaron. Decir “todos aquellos” es similar a lo que había dicho Helamán de sus soldados, cuando dijo que eran “hijos de aquellos hombres que Ammón trajo” (Alma 56:3). Es probable que Helamán le había enviado palabras similares a Pahorán. Cualquiera que sea la interpretación, Pahorán o no los menciona o los subestima. Debe notarse que quiénes sean “todos aquellos”, Pahorán no dice que reciban víveres, sino solamente que “que se mant[engan] firmes en esa libertad con que Dios los ha hecho libres”, o sea, que no se quejen, al cabo son libres, ¿no? Estas palabras suenan fuertes haciendo memoria del convenio hecho por los jóvenes ammonitas-lamanitas. Mormón había dicho que “hicieron un convenio de luchar por la libertad de los nefitas, sí, de proteger la tierra hasta con su vida; sí, hicieron convenio de que jamás renunciarían a su libertad, sino que lucharían en toda ocasión para proteger a los nefitas” (énfasis añadido; Alma 53:17). Pero Pahorán parece claramente estar citando las mismas palabras de Helamán. La frase de Pahorán es idéntica a las palabras de Helamán al final de su carta a Moroni. Describiendo a sus soldados jóvenes, Helamán dice que “permanecen firmes en esa alibertad con la que Dios los ha hecho libres” (Alma 58:40). Esta frase es igual a “todos aquellos que se mantienen firmes en esa libertad con que Dios los ha hecho libres” en la carta de Pahorán (Alma 61:21). Esto implica que Pahorán sí había recibido la embajada de Helamán que fue acompañada seguramente por una carta similar a la que Helamán le enviaría después al capitán Moroni.

Entonces, les estaba recordando (sabiendo que Moroni se lo comunicaría a Helamán) que estos jóvenes de sangre lamanita habían hecho convenio de dar sus vidas “para proteger a los nefitas”. Para esto los dos mil sesenta se habían alistado. Es extraño que Pahorán haya referenciado a los jóvenes ammonitas-lamanitas específicamente y las promesas que habían hecho. Seguramente sabía Pahorán que los soldados de Helamán eran la única compañía que era exclusivamente de sangre lamanita.

Aquí el capitán Moroni manifiesta su nobleza. A pesar del mandato directo de Pahorán de “obtener más víveres” y “fortalecer a Lehi y a Teáncum” solamente, “Moroni inmediatamente hizo que se mandasen provisiones a Helamán, y que también se enviara un ejército de seis mil hombres para ayudarle [a él] a preservar aquella parte de la tierra” (énfasis añadido; Alma 62:12). Por fin, Moroni (no Pahorán) manda provisiones y envía hombres específicamente para ayudarle a Helamán.

Conclusión

De esta manera Mormón muestra el etnocentrismo de los nefitas. Para muchos lectores modernos, es difícil imaginar que era la cultura nefita que trataba de esta manera a los soldados de sangre lamanita entre sus filas. Sin embargo, el registro de Mormón lo muestra de acuerdo con su cultura antigua.

Cuando la sociedad está en contra de uno o de un grupo en particular, se ve poca esperanza. En el ejemplo de los soldados ammonitas-lamanitas, su fe permaneció constante, la fe de sus madres. Aunque no dice nada Mormón al respecto, tiene lógica pensar que estos jóvenes sabían en cada circunstancia lo que pasaba por ser de descendencia lamanita. Igual que en todo el Libro de Mormón, el lector oye muy poco la voz lamanita. Por lo general, no sabe qué pensaban o creían Lamán (hermano de Nefi) y todos los que descendieron de él. Solo hay destellos (Alma 54:17). Los jefes de gobierno y los historiadores eran nefitas. La perspectiva en las páginas del registro es nefita.

Este estudio ha mostrado que el pueblo nefita controló y cambió el nombre del pueblo de Anti-Nefi-Lehi, sufrieron negligencia y fueron aislados como una compañía exclusivamente de raza lamanita. Al final de cuentas, Mormón está relatando la caída de su pueblo para una generación futura. El lector moderno debe prestar atención. Helamán y Moroni, aunque saturados en el mundo nefita, muestran su rectitud y nobleza al defender a estos jóvenes. Las enseñanzas de esta conducta, en lugares sesgada y en otras revolucionaria, permite al lector del Libro de Mormón ver su propia vida y descubrir los cambios que se deben hacer para que se vea la justicia de Dios en todo aspecto de la vida en esta generación futura.

Los jóvenes soldados anti-nefi-lehitas (el nombre que el pueblo había escogido para sí mismos) cae en el olvido. Mormón termina diciendo que “Moroni volvió a la ciudad de Zarahemla; y Helamán también se volvió al lugar de su herencia; y nuevamente quedó establecida la paz entre el pueblo de Nefi” (Alma 62:42). Estos jóvenes, quienes eran los protagonistas durante gran parte del registro no se vuelven a mencionar. Por motivo de que la mayor parte de su historia proviene de la carta de Helamán a Moroni y la de Moroni a Pahorán, parece indicar que no había más información sobre ellos en los anales nefitas. Es posible que por esa razón esta sección de la historia viene directamente de las cartas. No había más sobre los jóvenes soldados. Probablemente no era que Mormón no quería mencionar más de ellos sino que no había más detalles sobre ellos. Mormón dice después que estos conversos lamanitas sí habían guardado “muchos anales” pero no fueron incluidos en el registro nefita. Si no fuera por el registro de Mormón, los lectores no sabrían nada sobre este ejército ammonita-lamanita ni tampoco de la fe que ellos guardaron siempre.

“Y aconteció que muchos que eran del pueblo de Ammón, que eran lamanitas de nacimiento, partieron también para esa tierra. Y hay muchos anales de los hechos de este pueblo, conservados por muchos de los de este pueblo, anales particulares y muy extensos concernientes a ellos” (Helamán 3:12-13, énfasis añadido).

Introduction

One of the well-known and shared stories from the Book of Mormon that inspires faithfulness and the desire to put one’s “shoulder to the wheel” is about “two thousand stripling soldiers” (Alma 53:22). The story that inspires so many members of the Church is about how these young men were willing to trust in the faith of their mothers and put their life on the line for the safety and protection of the country ( Alma 56:47-48). This is an example of how God’s protection can be manifested with good leadership and focused diligence, inspiring trust in Him.

Yet, with a closer look at the context within these war chapters, there is more going on behind the scenes of this story that can go unnoticed by lay readers. The way in which Mormon, the historian, compiles and fleshes out the events of Book of Mormon history reflects ancient worldview of ethnic diversity. These two thousand stripling warriors always remained a military unit strictly of Lamanite heritage, based on Nephite ethnocentrism. Notwithstanding this isolation (segregation), they held to their faith and ultimately had success.

What’s in a name?

Mormon begins by telling the reader that he has “somewhat to say concerning the people of Ammon, who, in the beginning, were Lamanites” (Alma 53:10). It is possible that those who have not looked into the ethno-centric Nephite attitude will not see the message behind the titles given to this group of people. They “were Lamanites” before, but now were “the people of Ammon” (no mention of the title Anti-Nephi-Lehies [Alma 23:17]). The point being made is that they were not Nephites.

Throughout the history in the Book of Mormon, the wicked Nephites (and Zoramites) “became Lamanites” (emphasis added; Alma 43:4). Yes, many became “Lamanites, who were a compound of Laman and Lemuel, and the sons of Ishmael, and all those who had dissented from the Nephites, who were Amalekites and Zoramites, and the descendants of the priests of Noah” (emphasis added; Alma 43:13 see also Helaman 3:16). A wicked Nephite could become a Lamanite. In contrast, Lamanites could only stop being Lamanites by name; i.e., they “were no more called Lamanites” (emphasis added; Alma 23:17). They did not become Nephites, nor were they even called by that title. They continued to be Lamanites called by another name, and Book of Mormon history shows there was only equality when the “ites” were done away (4 Nephi 1:17).

Acknowledging this Nephite attitude, Mormon most certainly wanted to emphasize the fact that the two thousand young men “ called themselves Nephites” (emphasis added; Alma 53:16). They did not become Nephites, neither were they ever called by that name by anyone else. These faithful young men simply “called themselves Nephites.” That is how they identified themselves. Quite often, youth who have lived for many years in a country that is not their parent’s place of origin have done likewise. One grows up in a country and it becomes her/his own and its culture is ingrained in them. That new culture is blended with their parent’s culture. Here one can see that these young men were both Lamanites by blood and culturally Nephites in a Nephite country.

Several pages before, Mormon says that by the “fifteenth year of the reign of the judges” the people of Ammon were established in Jershon (in Nephite land; Alma 28:7). Then in the “the twenty and eighth year” these young men go to war (Alma 53:22-23), or perhaps it was “in the twenty and sixth year” (Alma 56:9). This means that they could have lived eleven to thirteen years in Nephite land. In addition, they were very young because Helaman calls them “my little sons” (emphasis added; Alma 56:30). They were still “little,” and they may have spent all their lives in Nephite land. That being the case, they had every right to “[call] themselves Nephites,” and more so after enlisting themselves to defend the Nephite country, that is, their country.

Even their foreign parents were calling this their home. When the war became oppressive, “they were moved with compassion and were desirous to take up arms in the defence [sic] of their country” (emphasis added; Alma 53:13) and “their brethren” (Alma 53:15). Not being able to fight due to their covenant to not take up arms, their children “entered into [a] covenant and took their weapons of war to defend their country” (emphasis added; Alma 53:18). Yet, Mormon observes that although they share a country the people are not as united as one would want today. When reviewing the covenant mentioned above, the language has these young identifying themselves as different from the other Nephites. “And they entered into a covenant to fight for the liberty of the Nephites … yea, even they covenanted that they never would give up their liberty, but they would fight in all cases to protect the Nephites and themselves from bondage” (emphasis added; Alma 53:17). They covenanted to defend the Nephites and themselves, making a distinction. Although they had “called themselves Nephites” they knew they were not like the other Nephites. Mormon says straightforwardly that they desired to defend their country but does not say they would protect their people (in reference to everyone in Nephite lands).

Ammoron doesn’t seem to face the same problem. When writing to Moroni, he proudly says, “I am Ammoron, and a descendant of Zoram, whom your fathers pressed and brought out of Jerusalem. And behold now, I am a bold Lamanite” (emphasis added; Alma 54:23-24). Ammoron could call himself both a descendent of Zoram and a Lamanite, and no one would disagree (Alma 43:13). The two thousand called themselves Nephites but nobody else did, not Helaman their leader, not Mormon the historian, not even their parents. The reader should not be surprised that nobody else ever calls them Nephites. This view of a sort of segregation, implemented by the Nephites is nothing new.

Nephite Ethnocentrism

Others have seen this inequality coming from the Nephites. Scholar John Sorenson, speaking of the integration of the Nephites in Mulekite lands, has said:

“The Mulekites are so little spoken of, although they composed a majority of the populace under the Nephite rulers (Mosiah 25:12), that we must suppose they constituted a peasantry who were ignored by the (Nephite) elite levels of society from which the historians came” ( Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book [Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013], 38).

One can notice in a close reading of the text that the Mulekites, identified as a people, almost disappear from Nephite history.

Commenting on the implementation of the word “desert” among the Nephites, Kirk Magleby has observed:

“If the central authorities in Nephi or Zarahemla did not exercise sovereignty over an area, it could be classed as wilderness. In other words, wilderness was frontier territory that lacked law and civilization (as defined by the authors of the text). For example, when Captain Moroni evicted the Lamanites from the east wilderness, they had built strongholds there Alma 50:11, but since they were not Nephite strongholds, chronicler Helaman 1 (abridged by Mormon) called the area ‘wilderness’” (Blog Book of Mormon Resources, “A Note about Wilderness” Monday, September 19, 2011 [accessed August 5, 2020]).

On the rejection of Samuel and his nickname “the Lamanite”, Max Perry Mueller has written:

“Samuel is turned away because Zarahemla is a segregated city. Yet, as Samuel’s prophecies indicate, perhaps Zarahemla is segregated based on degrees of righteousness as much as it is on shades of skin color. After all, the Lamanites have their own country, where ‘the more part of them,’ Mormon explains, ‘do observe to keep [the Lord’s] commandments, and his statues, and his judgments according to the law of Moses’ [Helaman 15:5-6]. … Samuel the Lamanite shouts from the walls of Zarahemla to the Nephites below, accusing them of rejecting him ‘because I am a Lamanite’ [Helaman 14:10]” (emphasis original; Race and the Making of the Mormon People [Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017], 50, 57).

Mueller also describes the manner in which the Nephites historians and religious leaders were rebuked by the Lord for not including in their record the prophecies of Samuel the Lamanite:

“Paradoxically, in the Book of Mormon it is not a Nephite but Samuel who prophesizes most accurately about the coming of Christ and the meaning of his earthly mission, death, and resurrection. … During his visit to America (around a.d. 34), the resurrected Christ examines the Nephites’ sacred text. And he finds them wanting. … Jesus Christ takes one look at the record and demands, where are the prophecies of ‘my servant, Samuel the Lamanite’? In a mocking tone, Christ asks Nephi3, ‘Were it not so’ that Christ commanded Samuel to ‘testify’ to the Nephites that Christ’s atoning sacrifice is available not only to all people everywhere but also to all people in every time? … On behalf of Samuel, Christ rebukes the Nephites for not having ‘written this thing’—Samuel’s prophecy—into the people’s sacred archive [3 Nephi 23:9-11]” (emphasis original; ibid, 49).

The Nephites had not kept neither had they held sacred the prophecies of a Lamanite. This reading of the text identifies the people of Nephi as being ethno-centric.

Also, the account of the people of Ammon is an appropriate example. When these Lamanites were converted to the Lord, Mormon says that “it came to pass that they called their names Anti-Nephi-Lehies; and they were called by this name and were no more called Lamanites” (Alma 23:17). They kept this name as long as they were independent (Alma 27:25), before descending to Jershon: “And they went down into the land of Jershon, and took possession of the land of Jershon; andthey were called by the Nephites the people of Ammon; therefore they were distinguished by that name ever after” (emphasis added; Alma 27:26). The name of Anti-Nefi-Lehi is not mentioned again until Mormon clarifies that this name, chosen for themselves, had been changed for another: “…[they] were the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi, who were called the people of Ammon” (Alma 43:11). And Mormon gives the reason why that name was abandoned (or taken away from them), a name they had chosen for themselves: “they were called by the Nephites the people of Ammon” (Alma 27:26). The Nephites had changed their name.

The verb “were” in Alma 43:11 can be interpreted in two ways: they “were” and continued being, or they “were” before but no longer. Mormon suggests that they received this name change upon arrival to Nephite lands. First, “the chief judge sent a proclamation throughout all the land, desiring the voice of the people concerning the admitting their brethren, who were the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi” (Alma 27:21). Soon afterward, Mormon says that “the people of Ammon were established in the land of Jershon” (emphasis added; Alma 28:1). In other words, they petitioned to enter as the “people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi” but were allowed to stay as the people of Ammon. This suggests that part of the “condition[s]” of entry (Alma 27:24) was to not be called “Anti-Nephi-Lehies”, perhaps not to be associated with the name “Nephi.”

It doesn’t stop here. The Nephites in Zarahemla say they will “give up the land of Jershon, which is on the east by the sea” for their possession (Alma 27:22). The Nephite record is clear that Zarahemla was found in “the heart of their lands” (Helaman 1:18). Therefore, following whatever model of Book of Mormon geography that the reader desires, if Zarahemla is in the “heart of their lands” then sending them to “the east by the sea” would have been to place them as far from the Nephite capital as possible. The Nephites did not only do this with the people of Ammon. Even after the people of Ammon had left Jershon (Alma 35:13), the Nephites continued to gather in one area any other Lamanite who made a covenant with them. Mormon later says that “when they [other Lamanites] had entered into this covenant they sent them to dwell with the people of Ammon” (emphasis added; Alma 62:17), Lamanites being sent to the Lamanite reservation. These young men grew up in a country that made a differentiation between Nephites and them.

Helaman and “the sons of those men”

For a leader, they choose Helaman (Alma 53:19), a noble man who would soon be a hero. However, no human being is perfect, and Mormon portrays Helaman’s formation/transformation. When writing to Captain Moroni, Helaman stressed the fact that these young men are not Nephites. In describing them, he says they are “two thousand of the sons of those men whom Ammon brought down out of the land of Nephi—now ye have known that these were descendants of Laman, who was the eldest son of our father Lehi; Now I need not rehearse unto you concerning their traditions or their unbelief, for thou knowest concerning all these things” (emphasis added; Alma 56:3-4).

Helaman does not say they are Nephites but says rather insensitively that they are sons of “those men” (i.e., the Lamanites). He didn’t even bother to identify them as the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi, who “Ammon brought.” Afterward, when these young men have success in battle, he tells Mormon, “never had I seen so great courage, nay, not amongst all the Nephites” (emphasis added; Alma 56:45). In other words, “never had I seen so great courage [among the Lamanites], nay, not [even] amongst all the Nephites,” making a distinction between the two thousand and everyone else. This is the same distinction these young men had made earlier (Alma 53:17). Certainly, Helaman did not do this consciously. It was merely a part of Nephite culture. Yet one can notice transformation in his words, against the norm, when he also highlights his relationship with them: “my two thousand sons, (for they are worthy to be called sons)” (Alma 56:10). Nonetheless, Helaman appears to feel it necessary to justify himself for calling Lamanites his “sons”: “for they are worthy.”

There is a passage that can be read in two ways, both favoring this reading of the text. When numbering their achievements, Helaman says: “we, the people of Nephi, the people of Antipus, and I with my two thousand” (Alma 56:54). The reader should remember that the original version of the Book of Mormon, transcribed by Oliver Cowdery, did not have punctuation. Therefore, it could be that the “people of Nephi” constituted the “people of Antipus” and “I with my two thousand,” according to modern punctuation. If this is the correct reading, Helaman includes these two thousand soldiers in the people of Nephi, a revolutionary concept. On the other hand, it is also possible that Helaman is distinguishing both groups, identifying himself with both: “we the people of Nephi [including] the people of Antipus and [in addition] I with my two thousand.” Helaman could be saying “we” to identify himself with the Nephites and then saying “I” to show that he is attached to the two thousand Lamanite company. Both readings work. Helaman may be making the effort to show Captain Moroni that the two thousand are part of the people of Nephi. Or, he could be making the same distinction everyone else.

Unknown Soldiers

If the above is an accurate reading of the events, there must be more particularities in the record that confirm this Nephite behavior. The text is clear that Moroni first finds out about these stripling soldiers through Helaman’s letter, found in chapters 56 to 58 of the book of Alma. Helaman begins by saying that “in the twenty and sixth year, I, Helaman, did march at the head of these two thousand young men” (Alma 56:9). Mormon says this happened in “the twenty and eighth year” (Alma 53:22-23). It was not until “the commencement of the thirtieth year of the reign of the judges, on the second day in the first month, [that] Moroni received an epistle from Helaman” (emphasis added; Alma 56:1). Depending on the date, whether the twenty-sixth or the twenty-eighth year, two to four years could have passed before Moroni, the captain of the army, even heard of Helaman’s miraculous company. For anyone who has served in the military, this sounds very strange, even for an army of ancient times. It is possible that the only ones in Nephite lands who knew about this group were the soldiers who fought along with them and their parents who had sent them off to war. (Later an argument for Pahoran’s knowledge of this Ammonite-Lamanite band of soldiers will be proposed.)

It is surprising that Captain Moroni did not know about them. On the other hand, it is arguable that king Ammoron was very much aware of this Ammonite-Lamanite company. Helaman wrote that he “received an epistle from Ammoron, the king” (Alma 57:1), perhaps having become the new military leader of the area after the death of Antipus (Alma 56:51). This letter came to nobody else. Therefore, the Lamanite king, of Nephite blood, may have known about Helaman’s band of stripling soldiers of Lamanite blood, while Captain Moroni was left in the dark. Although in war communication becomes difficult and distances are limiting, four years is a long time to not know about a group that has had so many miraculous successes in battle.

A Lamanite Company in a Nephite Army

Literally lines after relating to Moroni that they “were prepared with ten thousand men” (Alma 56:28) “Antipus ordered that I should march forth with my little sons to a neighboring city” (Alma 56:30). There were ten thousand men, counting or not the two thousand stripling soldiers and the order came that only the “little sons” of Helaman should go to Antiparah. That was their unit, ethnically unique. This was common anciently and there are cases in modern times also (WWII).

As the words of Helaman suggest, despite the reinforcements that arrived, this company of soldiers always ended up as ethically Lamanite unique. “And it came to pass that in the commencement of the twenty and ninth year, we received a supply of provisions, and also an addition to our army, from the land of Zarahemla, and from the land round about, to the number of six thousand men, besides sixty of the sons of the Ammonites who had come to join their brethren , my little band of two thousand. And now behold, we were strong” (emphasis added; Alma 57:6). Helaman states that the reinforcements came to “our army.” But, although various groups of thousands of soldiers came, they never stayed with his two thousand. Of all the thousands who came, only the “sixty of the sons of the Ammonites” actually remain with the two thousand.

The following maneuver leaves them once again abandoned. Helaman says that they resolved (“we did resolve”, suggesting that he was part of the decision) to “selected a part of our men, and gave them charge over our prisoners to go down to the land of Zarahemla” (Alma 57:16). Afterward, it is clear that none of the two thousand and now sixty accompanied this group chosen to go to Zarahemla because Helaman continued to have all of “my little band of two thousand and sixty” (Alma 57:19). After the arrival of six thousand men, the Ammonite-Lamanite company only received sixty and they happened to be of the same race as they. This is even after Helaman said he “joined [Antipus’ remaining men] to my stripling Ammonites” (Alma 56:57). They must not have remained “joined” for very long. Evidently, they were not simply a company in the Nephite army; they were a company exclusively of Lamanites in the Nephite army. At no point in time were Nephite reinforcements ever attached to the Ammonite-Lamanite band, perhaps until the problem was fixed.

Pahoran’s Indifference

It is likely that many readers have not seen these details before in the text. After many victories, the capturing of Antiparah (Alma 57:1-4) and Cumeni (Alma 57:7-12), Helaman expresses that he is not receiving the supplies that he needed, perhaps to maintain the recently seized cities. He informs Moroni that “the cause of these our embarrassments, or the cause why they did not send more strength unto us, we knew not” (Alma 58:9).

Captain Moroni adopts this problem and makes it his own. He sends a forceful letter to Pahoran, saying: “And now behold, I say unto you that myself, and also my men, and also Helaman and his men, have suffered exceedingly great sufferings; yea, even hunger, thirst, and fatigue, and all manner of afflictions of every kind” (Alma 60:3). It is difficult to imagine that Moroni had been suffering as the letter implies and only reacted this way after receiving Helaman’s letter. It is more likely that Moroni, as had Lehi and Teancum by the sea east (Alma 27:22 ; 52:18), had received both men and provisions. The area that had not received any was Helaman’s quadrant in the south by the sea west (Alma 53:22). Therefore, Moroni reacts this way due to the foul treatment of the soldiers under Helaman’s command. Mormon the historian says it also: “And it came to pass that he immediately sent an epistle to Pahoran, desiring that he should cause men to be gathered together to strengthen Helaman, or the armies of Helaman” (emphasis added; Alma 59:3). Neither Moroni, Lehi nor Teancum were in need of supplies. It was the armies of Helaman’s sector who had not received sufficient reinforcements from the government.

Even though Pahoran did argue that he had been dethroned by Pachus (Alma 61:3-5) and Moroni confirmed that it was true (Alma 62:6), Pahoran does not get off the hook so easily. The exchange between Moroni and Pahoran reveals that Helaman’s armies were not his priority. The reason for Moroni’s letter was to obtain provisions for Helaman, mentioning him by name three times (Alma 60:3, 24, 34). In stark contrast, in Pahoran’s letter, he does not mention Helaman once (Alma 61). Moreover, he suggests a plan for Moroni to rescue him and then take food only for Lehi and Teancum, ignoring completely Helaman’s problem and the purpose of Moroni’s letter. Anxiously and with a sprinkling of excitement, Pahoran says: “And we will take possession of the city of Zarahemla, that we may obtain more food to send forth unto Lehi and Teancum; yea, we will go forth against them in the strength of the Lord, and we will put an end to this great iniquity” (emphasis added; Alma 61:18). His last words manifest his true preoccupation: “ See that ye strengthen Lehi and Teancum in the Lord; tell them to fear not, for God will deliver them, yea, and also all those who stand fast in that liberty wherewith God hath made them free. And now I close mine epistle to my beloved brother, Moroni” (Alma 61:21). The armies that Pahoran wanted to strengthen were those of Lehi and Teancum only. Certainly, he must have had reason to be more preoccupied with the eastern front of the war, yet that does not justify ignoring Helaman’s situation completely. The text is not clear who Pahoran was addressing when he said “all those [men]” (see above). On the one hand, they could be the Nephite armies of Lehi and Teancum, and if so, he consciously ignored Helaman’s men. On the other hand, if “all those” is a reference to Helaman’s armies, Pahoran thought it not important to mention them specifically.

This may be, however, in reference to the Ammonite-Lamanite soldiers, seeing that Helaman had sent him an embassy earlier (Alma 58:4), whose men never returned. Calling them “all those [men]” harks back to Helaman’s words, when he called them “the sons of those men whom Ammon brought down” (Alma 56:3). Helaman may have sent similar words to Pahoran. Whichever the interpretation, Pahoran either doesn’t mention them or gives as little attention to them as possible. It should be noted that whoever “all those” are, Pahoran does not say that they should receive food, only that they should “stand fast in that liberty wherewith God hath made them free”; i.e., “Stop complaining, you’re free aren’t you?” These words ring strongly harking back to the covenant that these young Ammonite-Lamanites had made. Mormon had said that they had “entered into a covenantto fight for the liberty of the Nephites, yea, to protect the land unto the laying down of their lives; yea, even they covenanted that they never would give up their liberty, but they would fight in all cases to protect the Nephites” (emphasis added; Alma 53:17). Yet Pahoran clearly appears to be quoting Helaman’s own words. Pahoran’s phrase matches identically the words of Helaman at the end of his letter to Moroni. Describing his stripling soldiers, Helaman says: “they stand fast in that liberty wherewith God has made them free” (Alma 58:40). This phrase is identical to “all those who stand fast in that liberty wherewith God hath made them free” in Pahoran’s (Alma 61:21). This suggest that Pahoran had received Helaman’s embassy that was surely accompanied with a letter similar to the letter Helaman would later send to Captain Moroni.

Therefore, he was reminding them (most likely knowing that Moroni would tell Helaman) that these young men of Lamanite lineage had made a covenant to lay down their lives “to protect the Nephites.” These two thousand and sixty soldiers had signed up for this. It is odd that Pahoran would target these young Lamanites specifically and the promises they had made. Pahoran certainly knew that Helaman’s soldiers were the only company of Lamanite heritage in the whole Nephite army.

Here, Moroni shows his noble personality. Despite the direct command from Pahoran to “obtain more food” and “strengthen Lehi and Teancum” only, “Moroni immediately caused that provisions should be sent, and also an army of six thousand men should be sent unto Helaman, to assist him in preserving that part of the land” (emphasis added; Alma 62:12). Finally, Moroni (not Pahoran) sent provisions and men specifically to aide Helaman.

Conclusion

This was Mormon’s way of showing Nephite ethno-centrism. For many modern readers, imagining that it would be the Nephite culture that treated these soldiers of Lamanite heritage among their ranks in this way is a difficult endeavor. However, that is exactly what Mormon’s record shows according to its ancient culture.

When a society works against an individual or a particular group, hope is not visibly near. This example of the Ammonite-Lamanite soldiers highlights their faith in their mother’s convictions. Although Mormon is silent on the issue, it is reasonable to think that these young men knew in every circumstance what was happening because they were of Lamanite descent. Throughout the Book of Mormon, the reader seldom hears the Lamanite side of the story. She/he is generally ignorant to the thoughts and beliefs of Laman (brother of Nephi) and those who descended from him. There are only glimpses (Alma 54:17). The government leaders and historians were Nephites. The worldview found on the pages of the Nephite record is Nephite.

This study has shown that the Nephite people controlled and changed the name of the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi, they suffered negligence, and were isolated as company of Lamanite heritage. After all, Mormon is giving an account of the demise of his people for a future generation. The modern reader should take notice. Helaman and Moroni, though immersed in the Nephite world, show their righteousness as they defend these young men. By seeing their conduct, which at times is biased and at others revolutionary, allows the reader of the Book of Mormon to examine herself/himself and discover the changes that should be made to see the justice of God in all aspects of life in this future generation.

These Anti-Nephi-Lehies (the name they had chosen for themselves) disappear. Mormon finishes by saying that Moroni “returned to the city of Zarahemla; and also Helaman returned to the place of his inheritance; and there was once more peace established among the people of Nephi” (Alma 62:42). These young men, who had been center stage for the greater part of this story are no longer mentioned. Since the majority of these chapters come directly from Helaman’s letter to Moroni, and Moroni’s to Pahoran, apparently there was no more information about them in the Nephite record. It is likely that for that reason this section in the history is drawn directly from letters. There wasn’t anything else written about these stripling soldiers. It is likely that it wasn’t that Mormon didn’t want to write more about them, there simply was no more information on them. Mormon later says that these Lamanite converts, all the people of Ammon, did have “many records” but they weren’t included in the Nephite record. If it were not for Mormon’s record, readers would not know of this Ammonite-Lamanite army nor would they know of the faith that they always held near to them.

“And it came to pass that there were many of the people of Ammon, who were Lamanites by birth, did also go forth into this land. And now there are many records kept of the proceedings of this people, by many of this people, which are particular and very large, concerning them” – Helaman 3:12-13 (Emphasis added)

1. Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book [Salt Lake City y Provo, UT: Deseret Book y Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013], 38.

2. Blog Book of Mormon Resources, “A Note about Wilderness” Monday, September 19, 2011 [consultado el 5 de agosto, 2020].

3. Énfasis original; Race and the Making of the Mormon People [Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017], 50, 57).

Construimos una fe duradera en Jesucristo al hacer que el Libro de Mormón sea accesible, comprensible y defendible para todo el mundo.

Copyright 2017-2022 Book of Mormon Central: A Non-Profit Organization. All Rights reserved. Registeres 501(c)(3).EIN:20-5294264